How to write clearly and concisely

By Tom Browne

George Orwell once said that, ‘Good prose should be transparent, like a window pane.’ In other words, writing should be a tool for communication. It’s primary purpose is to get across ideas or concepts in language that everyone can understand.

Sounds easy, doesn’t it?

But the sheer volume of incoherent, mangled and downright boring writing out there shows that it’s far from easy. Far too often, inexperienced writers feel a need to show off their vocabulary, imagining that lots of adjectives and five-syllable words is the key to great copy.

Of course, it’s possible to dazzle and enchant people with your command of language, and plenty of great novelists, poets and playwrights do it all the time. If that’s what interests you, there are plenty of creative writing courses out there. And if you succeed in becoming the next Salman Rushdie, the Booker Prize awaits. I wish you the best of luck.

Succeeding in copywriting, however, requires a different approach.

It requires discipline, clarity and focus. And that means ditching the verbal cartwheels. No one is impressed if you know the meaning of triskaidekaphobia. You might want to drop it casually into conversation on a date, but it has no place in copywriting.

So how do you learn to write in a tidy, unfussy way? In truth, it takes a lot of time and practice—no one becomes an expert overnight. But here are five tips to get you started.

Do your research

If you don’t know what you want to say, then you won’t be able to write it. Some people try to bluff and bluster their way through, using their writing ability to cover up their lack of research (I was guilty of this at school). But with copywriting, there’s nowhere to hide.

Your job is to sell a product, business or concept. If you don’t know what you’re talking about, it will quickly show.

That’s why research must always come before writing. Gather all the information you can. Consult other people. Tackle the tricky questions. Before you pick up your pen, ask yourself, ‘What exactly am I trying to communicate here?’ That’s crucial advice when you find yourself trapped in a long-winded sentence and you don’t know how to get out of it.

FACT: A well-researched article pretty much writes itself. If your head is bubbling with thoughts and ideas that you’ve uncovered, they should flow naturally onto the page.

Once you’ve got a first draft down, you’re ready to move to the next stage…

Edit, edit, edit

Some people are nervous of even starting the writing process, or tear their hair out because they can’t think of a great opening sentence. It’s as if they expect a beautiful piece of writing to arrive fully formed. Occasionally that happens. But more often than not, you need to bash it a few times with a hammer.

We shouldn’t be surprised by this. If you want a beautifully carved marble statue, you have to start with a block of marble. So think of your first draft as that block of marble—it’s only going to turn into a well-crafted article once you start chipping away.

In my opinion, this is the most pleasurable part of the journey. You’ve moved beyond the Tyranny of the Blank Page and you’re beginning to see the shape of something interesting. At last, all that effort is about to bear fruit.

But it only works if you’re ruthless. This is no time for mercy.

All waffle must go. It doesn’t matter if you’ve written a beautiful sentence; does it serve the purpose of the article? If not, into the bin it goes. Drown your kittens. Kill your darlings. Remember, you’re writing for your reader, not yourself. And the reader will never know what you took out, just what’s left.

EXERCISE:

Describe your favourite TV programme or book in 400 words. Don’t think about it: just write whatever comes to mind.

Once you’ve done that, get out the editing scissors! Try to reduce what you’ve written to just 200 words.

When you’ve finished, compare the first version to the second.

I guarantee that the second version will be 100% more concise, clear and readable. Which brings us onto the next tip…

Don’t waste words

There’s a reason why Jane Austen was a novelist rather than a copywriter. Some of her sentences just wouldn’t past muster in the commercial world. (There are probably other reasons too, but let’s leave that aside.)

Take one of her most famous lines:

'It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife.'

It’s a good opening to a novel, admittedly. But for our purposes, it’s a bit long-winded. So how would a copywriter tackle the same sentence.

It is a truth universally acknowledged = Everyone believes

that a single man in possession of a good fortune = that a rich bachelor

must be in want of a wife = must want to get married.

So, in the final version:

'It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife.'

becomes:

‘Everyone believes that a rich bachelor must want to get married.’

OK, it’s not going to win any literary prizes. But the meaning is immediately clear, and you’ve reduced a 23-word sentence to a 11-word sentence—by more than half, in other words. If your overall word limit is only 200, that makes a big difference.

Jane Austen fans won’t like you, but that comes with the territory.

Ditch those silly rules

We all learn bad habits at university, but the most damaging is a style of writing guaranteed to bore everyone (apart from academics) to death. You know the kind of thing:

‘Pre-spacialities of counter-architectural hyper-contemporaneity recommits us to an ambivalent recurrentiality of antisociality, one enunciated in a degendered-Baudrillardian discourse of granulated subjectivity.’

Thankfully, most people don’t talk like this. But it’s merely an extreme example of language that’s stiff, codified and designed to obscure as much as illuminate. Quite often, people get hung up on how to say something, instead of concentrating on what they are saying.

If you find yourself in that position, you need to go back to basics. And a good place to start is all those petty rules imposed by teachers and grammar pedants everywhere:

Don’t start a sentence with a conjuntion (but, so, and).

Don’t end a sentence with a preposition (with, of, to).

Don’t split infinitives (to boldly go).

To be clear, these rules are total nonsense. In everyday speech, we start sentences with conjunctions all the time, and it feels just as natural on the page. So ignore the rule. And don’t let anyone tell you otherwise.

Star Trek would not have been the same if Captain Kirk and co had decided ‘to go boldly where no man has gone before’. And as for not ending sentences with a preposition, I’ll quote Winston Churchill: ‘This is the sort of nonsense up with which I will not put.’

FACT: Rules are there to serve writers, not the other way round. So if a rule gets in the way of simple communication, get rid of it.

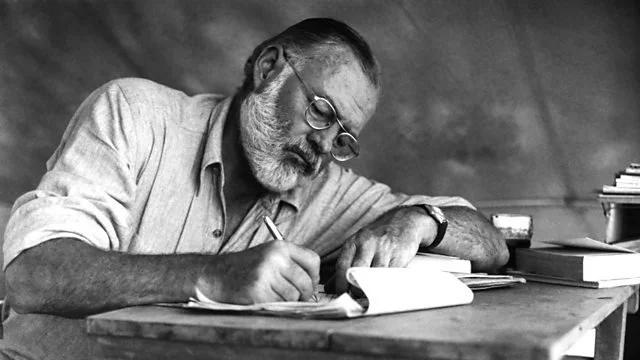

Become a better reader

No one chooses to make a living out of writing without a love of the written word. And just like any relationship, this love needs to be nurtured and renewed.

The bottom line: it’s difficult to be a good writer without being a good reader.

You need to learn from the best: the best journalists, the best novelists, the best poets, the best communicators. Your local library is stuffed full of great wisdom and learning, all thoughtfully rendered in beautiful prose. Why wouldn’t you take advantage of that?

Immersing yourself in books, newspapers and magazines feeds through to your work. Your brain will subconsciously learn the rhythms and cadences of good prose. Quality writing sings on the page; it feels smooth and effortless, like a well-oiled machine. Try reading it out loud and you’ll see what I mean.

Bad writing, on the other hand, is like a stuttering car crawling uphill and running out of petrol—you can practically hear the groaning, clanking and wheezing. You never want this to be said of your work.

So dive in forthwith. To quote William Faulkner, “Read, read, read. Read everything -- trash, classics, good and bad, and see how they do it. Just like a carpenter who works as an apprentice and studies the master. Read! You'll absorb it. Then write. If it's good, you'll find out. If it's not, throw it out of the window.”